GEOPOLITICS

The following is a submission that I made as my dissertation for my Master of Arts International Relations at the University of Kent. I had enjoyed every aspect of the research that I had carried out to make this project come alive. I thank my supervisor Professor Jamie J. Gruffyd-Jones who guided me all throughout the process. He himself is a powerhouse when it comes to China and its geopolitics. It was a great learning experience for me to be guided by him.

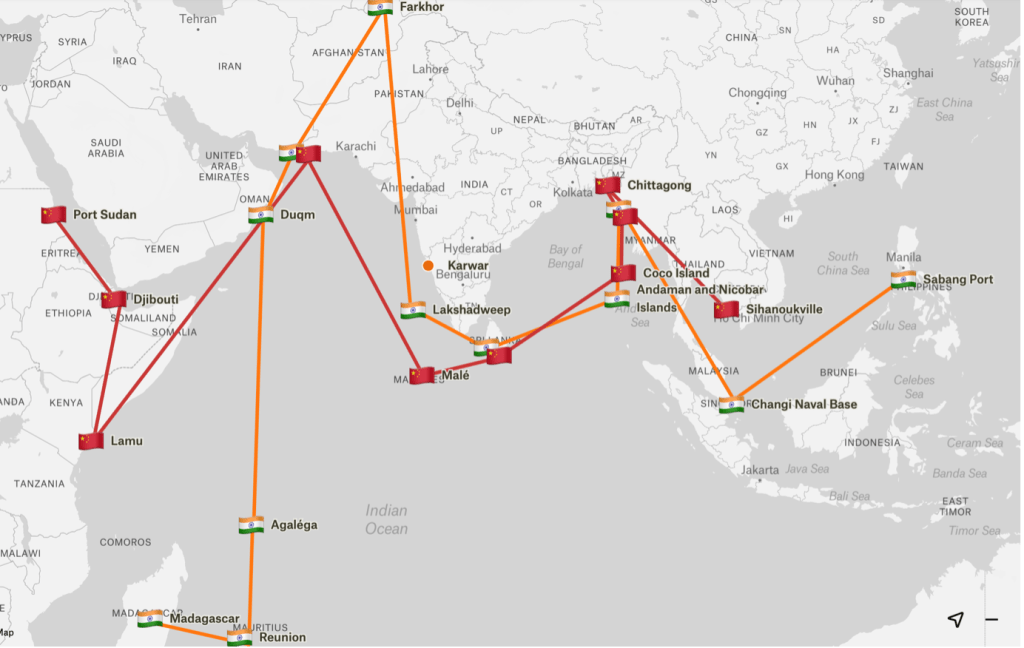

China’s ambitious “String of Pearls” strategy aims to secure vital shipping lanes and project global power through a network of commercial ports and potential military outposts along the Indian Ocean. The “String of Pearls” serves dual purposes: facilitating China’s economic interests and enabling a stronger naval presence to protect these interests, thus increasing its influence across the region. This has raised concerns among regional powers, especially India, about potential strategic encirclement, and spurred India to develop its counterstrategy, the “Necklace of Diamonds.”

The significance of studying the effectiveness of India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy lies in its critical impact on geopolitical stability and security in the Indian Ocean region. This region is a pivotal maritime corridor for global trade and energy transport, with significant strategic importance for both regional and global powers. By examining how India’s strategic initiatives counterbalance China’s “String of Pearls” using specific case studies, the investigation provides insights into whether India’s initiatives are effective in countering Chinese hegemonic designs and maintaining the balance of power. It will check if India’s strategy enhances maritime security and provide economic and diplomatic leverage in the region. This understanding helps policymakers and security analysts in formulating strategies that promote peace and stability in an area prone to geopolitical tensions.

Moreover, this study has broader implications for international relations theory and policymaking. It contributes to the academic discourse on maritime security, alliances, and power dynamics, offering empirical evidence on the effectiveness of strategic countermeasures in the face of rising regional hegemonies. For policymakers, the findings can inform strategic adjustments, enhance maritime cooperation frameworks, and guide investment in naval capabilities and infrastructure. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of economic and diplomatic engagements in complementing military strategies, underscoring the multifaceted approach required to address complex security challenges in the Indian Ocean region.

Aim of the Study:

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy in mitigating security concerns arising from China’s “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean region. By analysing key components of the Indian strategy, including naval modernization, strategic alliances, and the establishment of military bases, this research seeks to understand how India’s initiatives enhance its maritime security, economic influence, and diplomatic leverage. The study will employ theoretical frameworks such as Sea Power Theory and the Security Dilemma to assess the strategic interactions between India and China. Through case studies of specific locations like the Maldives, Philippines, and Mauritius, the research will provide a comprehensive evaluation of India’s approach. The findings aim to inform policymakers and contribute to the broader discourse on regional security dynamics and maritime strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

Background:

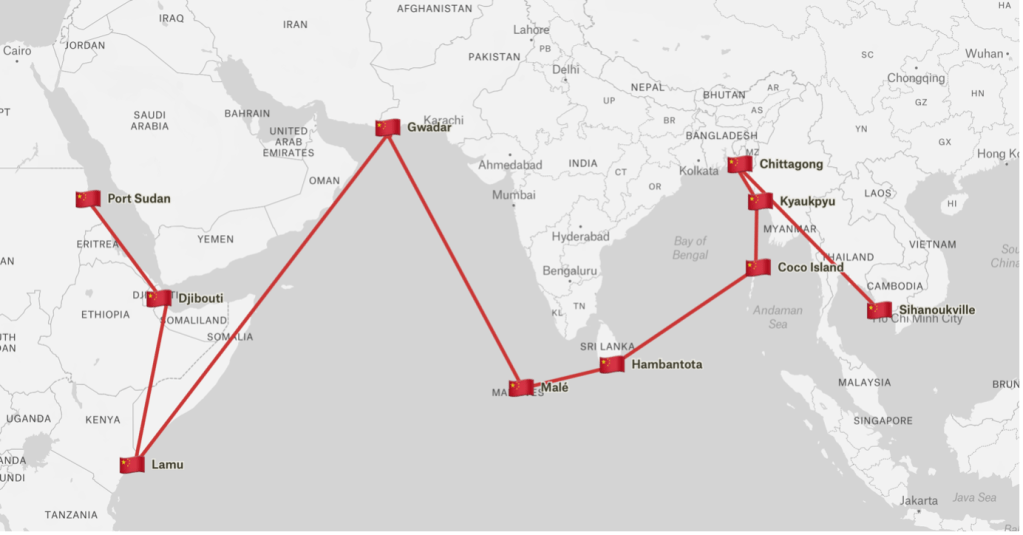

The network of naval bases and commercial facilities that China has built in and around Indian Ocean was first referred as ‘String of Pearls’ in a 2005 U.S Department of Defence report, which pointed out the encirclement of India (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). Key elements of this strategy are port development in Pakistan (Gwadar), Sri Lanka (Hambantota), Bangladesh (Chittagong), Myanmar (Kyaukpyu); infrastructure development like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); establishment of Military facilities in Djibouti and enhancement of diplomatic and economic ties with Indian Ocean littoral states. This strategy has strategic objectives like securing sea lanes, military power projection and extending China’s influences and alliances. But securing sea lanes is perhaps the key objective as Nicolas Weimar contends ‘the legitimacy and political fate of the Communist Party is closely linked to China’s continuous economic development and that is dependent on uninterrupted access to energy sources’ (D.Weimar, 2013) and these resources passes through Malacca Strait choke point which is a point of vulnerability for China. So, China must secure its SLOCs effectively for political and economic reasons. China has indeed established important presence in several port cities in the Indian Ocean, from Pakistan to Myanmar, dovetailing various relationships over the past decades, which certainly has been major irritant to India, intensifying the geopolitics in the region (Bastos, 2014). As a net effect of this strategy, the traditional hegemon in the Indian Ocean region, India, feels threatened by the increased Chinese interest in its backyard and has initiated its own strategy.

Figure 1:China’s String of Pearls Strategy

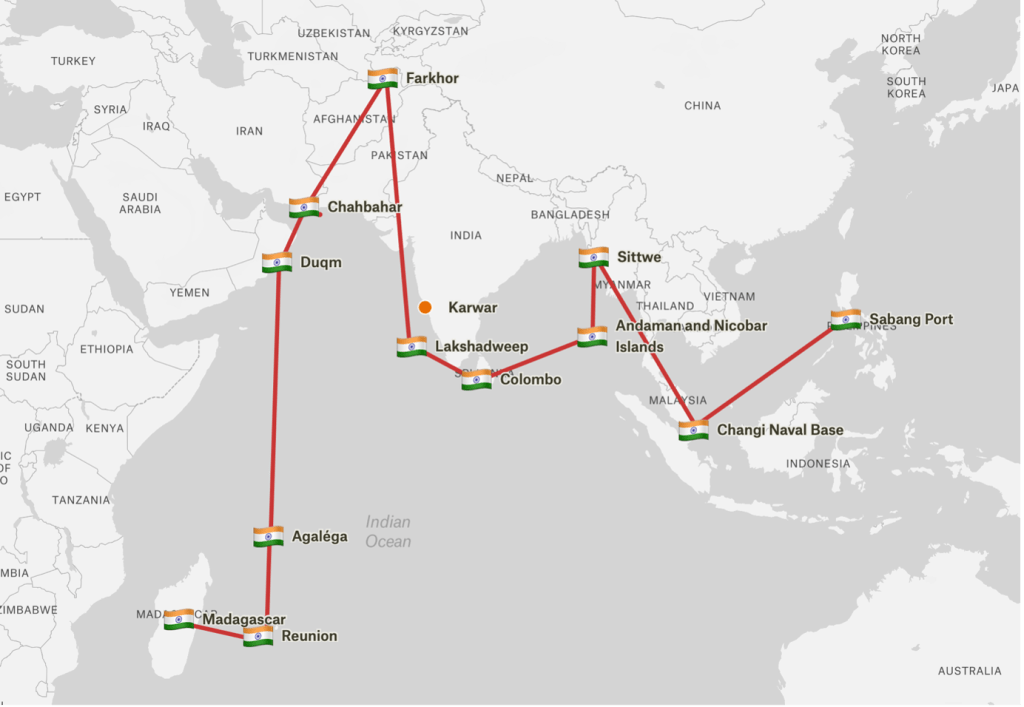

In response to China’s “String of Pearls,” India has developed the “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy, aimed at countering Chinese influence, and securing its own maritime interests through a network of alliances, strategic partnerships, and military bases. According to Gurpreet Khurana, increased Chinese naval presence in the region and possible military use of the bases suggests the strategic intentions of geographic encirclement of India (S.Khurana, 2008). The intentions of Chinese Military establishment is also very clear from the start, as General Zhao Nanqi, director of Chinese Academy of Military Sciences had asserted that they are not prepared to let the Indian Ocean become India’s Ocean, which is contrary to K.M Panikkar’s view of a ‘Truly Indian Ocean’ (Brewster, 2015). To counter this threat, former Indian Naval Chief Arun Prakash contends India’s options are less, either boost military muscle or strike alliances with willing partners (Prakash, 2007). This is exactly what India is doing. India seems to be pursuing an encirclement of China as well with key elements being Strategic bases at Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Seychelles, Mauritius (Agelaga) and Oman (Duqm); Naval modernisation through aircraft carriers, surveillance systems and submarines; Alliances and partnerships like the QUAD; economic and diplomatic initiatives like the Indian Ocean Rim Association or infrastructure projects. India has certain strategic objectives with regards to this plan like countering Chinese influence, securing sea lanes and maintaining regional stability. India is also cultivating partnership with like-minded partners like U.S, Japan, and Australia to bolster its efforts to counter Chinese rise in the Indian Ocean.

Indian Ocean Region and its significance:

Indian Ocean has always been important for trading and maritime security as one-third of the world’s cargo traffic and two-thirds of world’s oil flow through ply through this water body. This stretch of ocean from Africa’s eastern coast to Australia’s western coast is home to thirty-three nations and 2.9 billion people (Baruah, et al., 2023). In terms of trade volumes, Indian Ocean commands 80% of the world’s maritime oil, 9.84 billion tons of cargo pass through this region annually and almost $6.17 trillion dollars’ worth of trade was reported in this region in 2020 (Observatory for Economic Complexity, 2020). Besides the economic significance, this region has historical importance as well, as an important piece of history of humankind is situated in the Indian Ocean as it is believed that humans first went to sea in the Indian Ocean (Pearson, 2003). Ever since that, it has remained as a human ocean, a highway of trade, of prosperity, an ocean that transcended the various faith, cultures and enabled the mobility of people, ideas, and beliefs (Bose, 2006). The human dimension of Indian Ocean is one that needs to be sought to unravel the value it adds to human history.

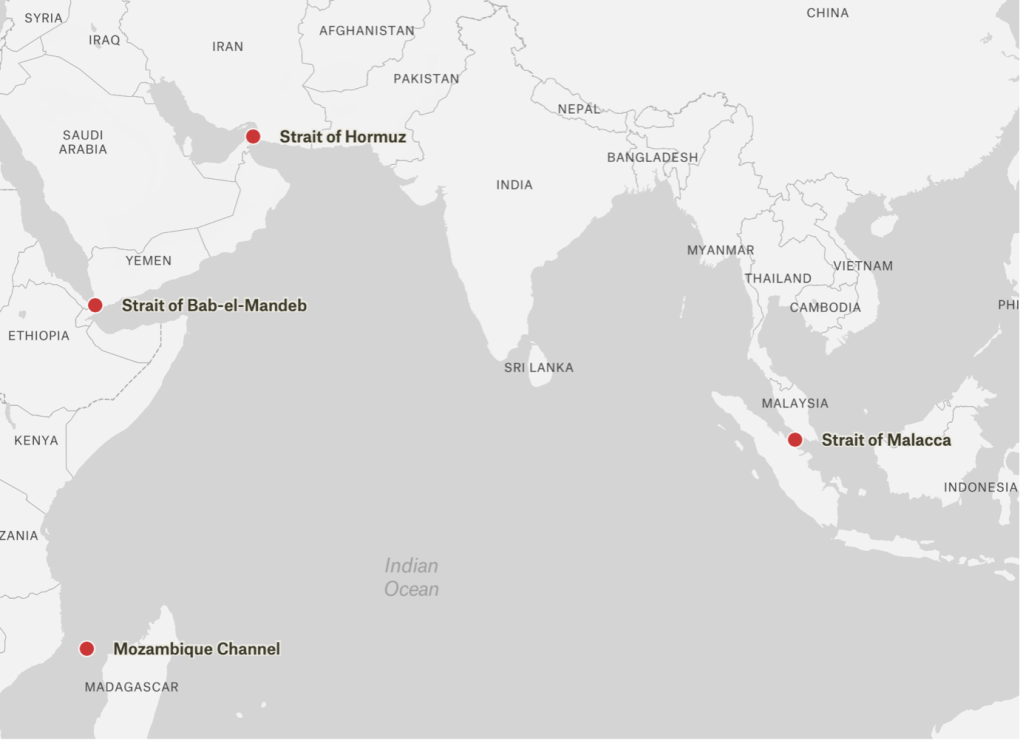

Another importance of Indian Ocean lies in its service as a ‘strategic highway’ that connects the Middle East, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Europe, and the Americas and is crucial for global economic security (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). Today, the strategic rivalries in the region revolve around maintaining military and strategic influence over the crucial chokepoints along the sea lines of communications (SLOC). Indian Ocean certainly has crucial choke points which are very vulnerable. It has 4 choke points, the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, and the Mozambique Channel. Through these choke points almost 36 million barrels of oil, which is 40% of global oil production, transit to their destinations (Baruah, et al., 2023). About 80% of China’s and India’s as well as 90% of Japan’s oil imports flow through these points, marking their importance for these countries. In fact, India’s 2004 Maritime Military Strategy declared the ‘control of choke points as bargaining chip in the international power game’ (Ministry of Defence, India, 2004).This leads us to the strategic interests of India and China in the region.

Figure 2: The Choke Points in the Indian Ocean region.

Strategic Interests of India and China in Indian Ocean:

The relation between two main power stakeholders in India and China is conditioned by the fact that both Asian heavy weights are having unprecedented levels of growth, have the capability to influence global markets and have high ambitions at international political arena (Bastos, 2014). The two growing nations often depicted as Tiger (India) and Dragon (China) have designs to assume hegemonic positions regionally and a more interventionist role in the international political affairs. They are pursuing geo-strategic manoeuvres, mostly for one reason: Energy Security. From this vantage point, the strategic rivalries, in the region revolves around maintaining military and strategic dominance on the crucial chokepoints on the Indian Ocean, where countries nestle and jostle to secure and deny others free navigation (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). For India, Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is crucial, as 80% of its crude oil and 95% of trade are transported via these waters. India depends on more than 70 % imported oil and this number is expected to increase to 90% by 2025 (Agnihotri, 2012, p. 15). India’s trade with littoral states in IOR grew exponential in the last decade, becoming the 4th largest trading partner by 2007 (Gupta, 2010).Therefore, free access across these waters is key for India’s continued growth. Ever since independence, India understands this importance, especially evident through the words of pioneer Indian Geopolitician K. M Panikkar argued that ‘as India’s future was dependent on the Indian Ocean, it must remain truly Indian’ (Rumly, 2012). Indian Navy identifies the entire Indian Ocean as its area of priority, underpinning its role as first responder as well as net security provider to its allies and partners in the region (Baruah, et al., 2023). As part of strategic engagements, India has signed many agreements with Sri Lanka and Maldives and other littoral states under Modi government’s Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) initiative. As a resident power in the Indian Ocean, India attaches exceptional value to the ocean and its freedom to navigate its waters.

Chinese presence in the region can be traced back many centuries particularly to the voyages during the times of Ming dynasty. Today, nearly 70% of China’s oil imports pass through the Indian Ocean, facing several choke points, particularly Malacca Strait (Bastos, 2014, p. 22). Presence of US bases in around the region makes Chinese policymakers insecure about the SLOCs. China’s 33% of sea trade worth more than $300 billion each year pass through these waters (S.Khurana, 2008). As China is an important manufacturing hub, it is dependent on open trade routes with African and Indian Ocean littoral states for supply of raw materials and minerals. Also, China is the top import partner for 24 countries in the Indian Ocean and the top export partner for 13 countries in the region (Carnegie , 2024). Its investments and development projects have furthered its partnership in the region, key recipients being in Africa, East Asia and South Asia under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It also has the greatest number of diplomatic missions in the region.

China’s strategy focuses on establishing a network of ports with potential military applications, while India’s strategy emphasizes strengthening its naval bases and enhancing regional security cooperation. Both strategies aim to extend the respective country’s influence in the Indian Ocean region through strategic partnerships and infrastructure investments. China’s BRI-related investments are a key component of its strategy, whereas India focuses on regional cooperation and economic projects to foster stability and growth. Both strategies reflect the growing importance of the Indian Ocean in global geopolitics and the ongoing competition for influence between China and India in this critical maritime region. The success of both strategies relies on factors beyond just building ports. India’s “Necklace” hinges on effective diplomacy, ensuring partner nations see India as a reliable and long-term ally compared to China’s transactional approach. Ultimately, both the “String of Pearls” and “Necklace of Diamonds” reflect the growing strategic competition between China and India for influence in the Indian Ocean, a vital region for global trade and security.

Chapter 2: Literature Review and Research Design

2.1 Review of Literature Consulted:

Ever since early 2000’s, many scholars have studied and analysed the emerging competition between India and China in the region. The have critically engaged with factors that have contributed to these strategic tensions between the Asian heavyweights. Existing scholarship in this field has extensively investigated the history, geostrategic implications and strategies used by both India and China to outmanoeuvre each other in the Indian Ocean region. One of the well-researched perspectives by (Pant 2014) has provided key military and strategic implications of China’s rise vis-a-vis India in IOR. He has analysed this phenomenon right from the start and predicted a fierce competition between the powers. The second paper consulted was by (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024), where they have analysed the underpinnings of the strategic rivalry, which is maintenance of military and strategic dominance over the key choke points in the Indian Ocean region. It also gave insight on the naming of China’s strategy as ‘String of Pearls’ originated in a 2005 U.S. Department of Defence report. It mentions the reason why India is apprehensive about Chinese presence and gives account of Indian response to the threat, which includes security infrastructure and military asset build-up, compares it with China.

The third paper by (Bastos, 2014) speaks from a slightly Chinese perspective where the author predicts that neither country can sustain high levels of confrontation for long because of the incurring economic and domestic losses. This paper briefly gives account on the human history in the Indian Ocean and how India and China evolved in the region. This paper also suggests that India is also encircling China as well and underpins ‘Energy Security’ as the core reason for these strategic moves by both powers. It also claims that most of the tensions between these powers are exaggerated by Western media and academic circles to discredit the emerging multi-polar world order. Fourth paper by (Sokinda, 2015) analyses India’s strategy for Countering China’s influence and gives a glance of India’s options. It asserts protection of China’s economic growth is linked to Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy as the major motivation for Chinese manoeuvres in the region. Enlightened by many military and academic scholars of both Western and Asian origin, this paper was delightful to read because of the sheer insights it had provided. Given the fact that this paper was produced for the Vice Chief of the Defence Force, Australia, such quality was always expected. Another key literature is by (Mengal 2022) has extensively explored the key projects that India and China are investing to balance out each other. Yet, he has not dwelled upon the other areas of competition that both countries are engaged in like Aid diplomacy, ocean surveys, arms testing, construction deals in littoral states and elsewhere to name a few.

After analysing these academic papers, I found that, most speak from a strategic or economic perspective on why such competition emerges and fails to provide a comprehensive outlook on whether India’s strategy is effective in dealing with Chinese rise in the region. It fails to provide account on crucial factors such as political climate, influence of economic aid and effects of external influence on Indian Ocean littoral states which underpins the success of India’s ‘necklace of diamonds’ strategy. For instance, (Pant, 2014) has not addressed the economic and political evolution of this competition in the littoral states of the region and effectiveness of Indian initiatives. Thus, these papers cannot pinpoint the reasons why India’s approach was successful or failed in some cases. Also, most papers do not explore the potential of India’s offshore balancing strategies with like minded powers against China. Thus, I am exploring these aspects of this emerging competition between India and China to print a more comprehensive, yet concise analysis and check whether India’s strategy is effective.

2.2 Theoretical Framework:

This research revolves around the Maritime security of both India and China. Today, maritime security has become a buzzword that get featured in all strategy documents of major actors like European Union, the United Kingdom and NATO (Bueger, 2015, p. 159). The definition of maritime security is in constant flux as it is dependent on what the actor tries to prioritise. As (Bueger, 2015), points out, the meaning can include factors of sea power, marine safety and recently for many small island nations, it also includes blue economy and resilience. Therefore, it is harder to define exactly what constitutes Maritime security. Also, it is noted that the wider the understanding of maritime security, the wider the range of actors involved.

Realism views states as the primary actors in international relations. Maritime security is thus a matter of national interest and sovereignty. States seek to secure their maritime boundaries to protect their territorial integrity and economic interests (Mearsheimer, 2001). Realists emphasize the importance of military capabilities, particularly naval power, in securing maritime interests. A strong navy is essential for deterrence, power projection, and protecting maritime trade routes (Till, 2018). They also posit that the international system is anarchic, leading states to maximize their power to ensure their survival. Control over strategic maritime chokepoints and sea lanes is crucial for maintaining a balance of power (Walts, 1979).

Whereas the idealist perspective in international relations emphasizes the role of international law, cooperation, and institutions in achieving security and peace (Axelrod & Keohane, 1985). Idealism stresses the importance of cooperation among states to ensure maritime security. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a cornerstone of this approach, providing a legal basis for resolving disputes and regulating maritime conduct. Idealism promotes the concept of collective security, where states work together through international organizations like the United Nations to address maritime security threats. This approach emphasizes shared responsibility and collective action (Claude, 1956).

In this research, I am seeking to check the effectiveness of India’s strategy using these theories:

Sea Power Theory:

This theory, primarily articulated by Alfred Thayer Mahan, provides a foundational framework for evaluating the effectiveness of maritime strategies like India’s “Necklace of Diamonds.” Mahan emphasized the importance of naval dominance, control of strategic maritime chokepoints, and the ability to protect maritime trade routes. Evaluating the “Necklace of Diamonds” using Sea Power Theory involves assessing how effectively India’s strategic initiatives enhance its maritime influence, security, and ability to counterbalance Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean region. Key concepts of this theory: 1) Control of Strategic Locations like choke points, 2) Naval Strength and Capability 3) Maritime Commerce: Protection and facilitation of maritime trade as a vital component of national power (Mahan, 1898). 4) Alliances and Bases: Establishment of alliances and overseas bases to project power and maintain a presence in strategic regions (Till, 2009).

India has always flirted with Mahanian principles, as many Indian commentators opened their writeups with this quote “Whoever controls the Indian Ocean dominated Asia. The ocean is key to seven seas. In the 21st century the destiny of the world will be decided on its waters’( (Rai, 2001), (Singh, 2003) (South Asia Foundation, 2000), (Prakash, 2007)). The attribution might have been a misinterpretation of Mahan’s statement, yet it underpins India’s current strategic visions (Scott, 2006). Prominent Indian historian and diplomat K. M Panikkar has argued that for India, the Indian ocean is a vital sea, and it is in its interests that the ocean remains truly Indian (Panikkar, 1945, p. 12). So, it is apparent that India do desire an outright hegemony in the Indian Ocean given its drive to establish bases and modernisation of its navy. Using this theory, I would try to understand India’s motive to acquire more outposts in the region and influence its partners to counter China’s rise. I would use these theories test out the effectiveness India’s initiatives and how they interact with India’s ambition to maintain its hegemony in the region. It can clearly explain India’s strategic designs for the region and its motivation to sustain its supremacy in IOR, given its significant geographical advantage, on the eve of Chinese surge.

Security Dilemma Theory:

This theory is a fundamental concept in International Relations that describes how actions taken by a state to increase its security can lead to increased insecurity among other states, prompting them to take similar measures, first articulated by John H. Herz in 1950 (Herz, 1950). This often results in a cycle of escalating tensions and an arms race. This theory has suitably used by many scholars to explain the spiralling rivalries in international realm like (Waltz, 1979) on Cold War Arms race, or action-reaction dynamics between states by (Glaser, 1997). In the context of evaluating the effectiveness of India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy, the Security Dilemma theory can provide valuable insights into the strategic interactions between India and China in the Indian Ocean region. By examining case studies, it can reveal that India’s strategic initiatives often lead to increased regional tensions and counteractions by China. This cycle of action and reaction underscores the complexity of achieving enhanced security in a highly competitive and interconnected geopolitical landscape. It is also applied on specimen countries, where in some cases effectiveness of India’s strategy has been limited by local opposition and the broader regional security dynamics. The inability to fully implement the base development reflects the challenges posed by the Security Dilemma, where attempts to increase security led to heightened insecurities and resistance. Thus, giving policymakers insights on the deleterious effects of security maximisation and how it may lead to further intensification of insecurity and tensions.

2.3 Research Design:

To establish how India’s strategy of “Necklace of Diamonds”, which is the independent variable, is mitigating the security concerns arising from China’s presence in Indian Ocean, which is the dependent variable, I intend to use Mixed methods of comparative study on strategies of both countries. Comparative study is the most widely used methods in political research and used to study a wide range of political phenomena (Halperin & Heath, 2017). One of the key strengths of comparative study is that it helps to broaden our intellectual horizons. It can help us to save us from twin dangers of false uniqueness and false universalism, where the former emphasises the specificity of the case while ignoring the general social factors whereas the latter assumes that the theory tested in one case will be equally applicable to other as well (Rose, 1991). Here in this research, I will be comparing India’ strategy against Chinese one, with special emphasis on ascertaining the effectiveness of the former. I believe comparative study is most suited in this case as it will shed light on the evolution of competition between India and China. Comparative analysis of both strategies involves looking at the data on investments, military presence, and regional influence. I have supplemented the analysis by incorporating quantitative data on security indicators like military exercises conducted in the region, access and servicing agreements signed between interested parties in the region etc.

The data that I am going to utilise is secondary data that is sourced from academic papers, government reports, maritime security doctrine reports and reliable news articles that are specifically made on this topic. With regards to data analysis, I intend to use mixed methodology where both qualitative and quantitative analysis will be carried out to ascertain the validity of the data that I shall collect for my research. This will improve the reliability of the data that is utilised for the research. I will quantify the effectiveness of Indian strategy based on the indicators like military assets deployed, positive government interactions like naval exercises between stakeholder countries, quality of aid and assistance provided and overall goodwill that is visible in favour of India, that ensures security of its interests in the region.

Within this, I intend to use some case studies, where the “Necklace of Diamonds” have been implemented in strategically important countries in the region, to analyse its effectiveness. Case studies remain one of the main research forms in Comparative politics (Geddes, 2003). More commonly, case studies are used to apply theory from one context to see if it still holds in the other contexts (Halperin & Heath, 2017, p. 215). They are an incredibly useful tool to examine whether concepts and theories travel and whether they work in the same way in cases other than they were originated. While selecting the case studies, I am mindful of the two main criteria laid down by (Geddes, 2003) i.e. i) that case should provide fair test of the theory involved, ii) the cases used for testing arguments should be different from the cases from which arguments were induced. As a prelude to current Indian actions, many leading Naval officers like Former Commander of Western Fleet Manohar Awati invoked Mahanian principles, where he called for Naval expansion and establishing geostrategic relations with Mauritius, the Reunion, Seychelles, and Maldives (Awati, 1993, p. 82). Based on that I have selected case studies to check the effectiveness of India’s ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ in Mauritius, Philippines, and Maldives. Philippines was added to check India’s influence beyond IOR as it is located at the backyard of China in South China Sea, thus enabling me to investigate the Security Dilemma theory. Each country is selected based on the strategic importance that it entails to India’s grand plan, and, in each, I will apply the theory of Sea Power and Security Dilemma, to understand the way each country responds to India’s strategy, how effective was India in achieving its security goals. These case studies will reveal the factors that influence these nation’s decision making and how that has a profound impact on the effectiveness of India’s strategy. So, the comparison does not only consider the sheer number of military assets deployed by India and China, or the size of investments and aid provided by each country in the region, but also goes in deep to analyse the effect of these in strategically important countries in the region. This way, I intend to print a comprehensive picture on the evolving competition and specifically the effectiveness of India’s ‘necklace of diamond’ strategy.

Chapter 3: India’s Strategic Initiatives in the Indian Ocean

In this Chapter, I intend to explain about India’s strategic ambitions in the region to set the stage for its reasoning of ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ strategy. Then I would be taking you through the nuances of India’s strategy, explain about its strategic bases and alliances developed, Naval modernisation efforts, key intelligence infrastructure deployed, exercises conducted with other likeminded nations, diplomatic engagements, and foreign policy initiatives to bolster India’s Maritime security. I would also ascertain the effectiveness of this strategy by exploring both its strengths and weaknesses. By the end of this Chapter, you will be given a comprehensive picture of India’s strategy and its overall effectiveness in countering the Chinese surge.

3.1 India’s ambitions in the Indian Ocean region:

India’s ambition for the Indian Ocean region stems from insecurity that it faces when it undermines its valuable position. As brazenly put forward by the then Commander of Western fleet of the Indian Navy, Kailash Kohli, in 1996.

“History has taught India two bitter lessons: firstly, that neglect of maritime power can culminate into cession of sovereignty and secondly, that it takes decades to revert to being a considerable maritime power after a period of neglect and decline. (Kohli, 1996)”

This argument underpins India’s desire to wield ambitious naval prowess, particularly in its backyard. The physical background for India is that, only very few nations in the world geographically dominate an ocean area as India in Indian Ocean (Misra, 1986) and that drives India’s desire to impose Mahanian style sea power through control and access to key points, bringing with it power projection, denial of access to rivals and control of choke points (Scott, 2006). As a rising Great Power, India have hopes of its own hegemonic sphere, its own backyard of power and pre-eminence. This gets reflected in Indian Maritime Doctrine of 2004, where it talks about India’s maritime destiny and vision, and sets benchmarks like need for sea-based nuclear deterrent, revised naval posture away from coastal protection to a more assertive competitive strategy of enabling Indian Navy to engage and counter distant emerging threats and protect sealines of communications (Majumdar, 2004).

Now with China pushing its influence directly into Indian Ocean and challenging India’s hegemonic position, India is forced to act. The apparent possibility of China’s infrastructure development in and around India’s periphery, be it Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, or Chittagong in Bangladesh, to be used for Military purposes, New Delhi is not going to sit idle and let China have its way in its backyard. The Chinese development may be a legitimate reflection of Chinese commercial interest, but somewhere in Indian strategic circles, there is a strong belief in that it is either an encirclement of India or is intended to keep India strategically preoccupied in South Asia (Brewster, 2015).

K.M Panikkar had argued for an Oceanic Policy that sort of resembles a steel ring that ties together India’s strategic areas of interest, with islands in Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea, including Mauritius, Singapore and cautioned against resurgent China (Panikkar, 1945). Today, one can safely assume that India’s “necklace of diamonds” inherits this spirit, though none of the official Indian Naval documents has any mention of this strategy being spelt out so blatantly. Same applies to China’s strategy, as one wouldn’t any official documents on it as well. Yet the competition between these Asian heavyweights is for all to see.

3.2 India’s Strategic Bases:

The Chinese actions in the Indian Ocean especially under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has exhorted both New Delhi and several Western Capitals to take the encirclement threat seriously (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). While China’s use of these ports may be for commercial purposes, yet the possibility of them being used for military purposes is a source of alarm for New Delhi. Beijing’s involvement in building Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar, for instance can challenge Indian Navy’s dominance in Bay of Bengal, Chinese military base in Djibouti unveiled in 2017 and possible militarisation of Gwadar port in Pakistan can turn into a security nightmare for India. Increasingly China’s actions have not been in line with the repudiation of encirclement and only feeding into India’s fears. First the acquisition Hambantota Port for 99-year lease, when Sri Lanka couldn’t service the debt, was increasingly seen as part of Beijing’s debt-trap diplomacy. To add to the suspicion, in 2022, a Chinese spy ship docked at this very port and New Delhi was furious about it (Tan, 2022). In fact, India has every reason to fear this docking as these ships could track its missile tests and gauge its performance using its onboard sensors, and Bay of Bengal is India’s Missile test ground adds to the India’s fury. New Delhi had to cancel certain missile tests in 2022-23 after issuing NOTAM warnings as it tracked Yuan Wang ships entering the Indian Ocean (Balakrishnan, 2024).

These developments have set in motion a counter reaction from India, that is to develop bases and ports within and outside its territories. Some of the key anchor points of India’s Necklace of Diamond strategy are Lakshadweep Islands : INS Jatayu Naval Base developed by India to act as an outpost in Arabian Sea, Andaman and Nicobar islands are being developed as unsinkable aircraft carriers (Chopra, 2022) to counter Chinese development in Myanmar, Bangladesh and can keep a close eye on Malacca Strait as well. Besides this India has neutralised Gwadar’s effect by establishing similar port in Chahbahar in Iran, Djibouti base with Duqm base in Oman (Basak, 2022), opening the airbase and jetty in Agaléga Islands, Mauritius has given New Delhi a vantage point over the major SLOC’s in Indian Ocean, whereas India is currently developing West Colombo port as an answer to China’s Hambantota Port in the same region and Sittwe Port in Myanmar is its answer to Kyaukpyu and Chittagong ports of China in Myanmar and Bangladesh respectively. Extending beyond the IOR, India has access and servicing agreement with Singapore to use the Changi Port situated at the mouth of the Malacca strait and regular naval exercises are conducted by both navies and air forces in this region, whereas Sabang Port in Indonesia extend India’s reach well into South China Sea, again facilitated by an access and service agreement with Indonesia. These moves of India to develop ports and bases in and around Indian Ocean to bolster its maritime security depicts the Sea Power theory in action, whereas India’s reaction to Chinese developments and actions, point towards an escalation fuelled by fear which is line with Security Dilemma theory.

Figure 3: India’s ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ Strategy.

3.3 Boosting Maritime Capabilities:

Not just with bases and ports, India is also taking on China in terms of sheer number of military assets deployed and crucial infrastructure being developed to protect its maritime interests. The Indian Naval Doctrine 2015 have displayed an evolution of strategy from emphasis on freedom of navigation in 2004 Doctrine to the concept of being ‘net security provider’ (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). The naval strategies also evolved from prioritising ‘sea control’ to emphasising ‘sea denial’, with acquisition of long-range submarines. Sea control means ensuring dominance in maritime territories whereas sea denial is tactic to neutralize an adversary’s war-waging capabilities by preventing them from accessing critical areas. This is a huge departure from the past, as post-independence until the end of Cold War, India curtailed its influence within the Indian sub-continent depicting India’s Monroe Doctrine (Sokinda, 2015). Today, Indian Navy is on track to become a blue water navy by inducting many naval assets. It has beefed up its naval budget, the largest increase in the overall defence budget in 2023 was for the navy to modernise its warships, augment its fleet and innovate new technologies. India has inducted its 2nd Aircraft Carrier called INS Vikrant in 2022, 6 French Scorpène submarines (Kalvari Class) and is set benefit from the purchase of MQ-9B Sea Guardian drones (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). Let’s look at the number naval assets both India and China have.

Table 1: Comparison of Naval Power.

| Type of Naval Asset | Indian Navy | Chinese Navy |

| Aircraft Carrier | 2 | 2+ (1) |

| Amphibious Transport Dock | 1 | 8 |

| Tank landing docks | 4 | 36 |

| Destroyer | 12 | 49 |

| Frigates | 12 | 42 |

| Nuclear-Powered Submarines (SSBN) | 2 | 7 |

| Nuclear Attack Submarines (SSN) | 0 (1 on lease to join in 2025) | 9 |

| Conventional Attack Submarines (SSK) | 16 | 45 |

| Corvettes | 18 | 72 |

| Landing craft utilities | 8 | 36 |

| Off-shore Patrol Vessels | 10 | 57 |

| Fleet tankers | 5 | 17 |

| Total* | 132 | 370 |

*Figure does not include both coastal and ocean-going auxiliaries, from tugboats to hospital ships. Not counted towards total number of active ships. Data from Indian Navy (Archive, 2024), Chinese Navy (Haijun360, 2024).

Of course, India cannot match the Chinese Naval power, but what matters is the Chinese Navy’s ability to deploy its ship far beyond its periphery into the Indian Ocean. With tensions rising in South China Sea due to Taiwan, and other peripheral states, China can only deploy so many ships to challenge the Indian Navy in its backyard, with only 6-8 Chinese ships deployed against little more than 35 ships of the Indian Navy (Ray, 2024). Recently, there has been an uptick in Chinese Deployment in IOR, with 12-15 ships deployed in a year (Indian Express, 2024). This prompted India to undertake various Naval Modernisation efforts, where currently 67 warships are under construction that include destroyers, frigates, and submarines to boost numbers to 200 ships and 500 aircrafts by 2050 (Press Trust of India, 2023). Strategic assets like American P8-I Poseidon aircrafts and drones like Israeli origin Heron 1, aid Indian Navy to keep an eye on China.

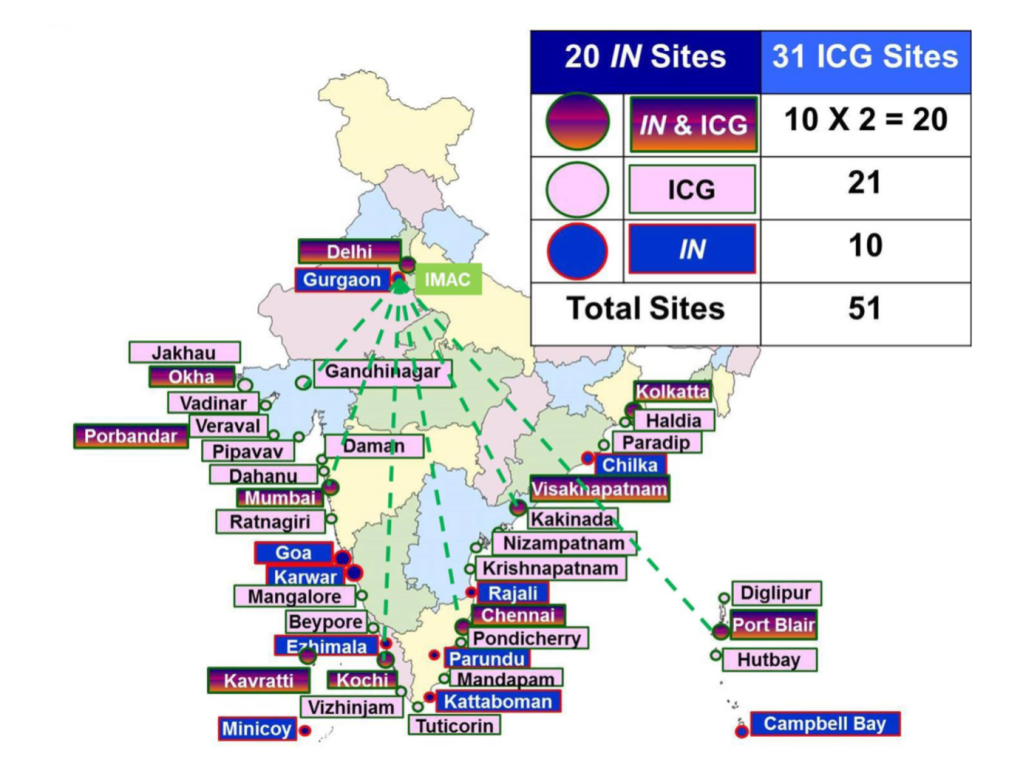

Figure 4: Location of Coastal Radars in India. Image courtesy: (Chawla, 2016)

In terms of institutional preparedness, India has set up many coast radar stations across its coastal areas as well as in many littoral states. The system that is deployed by India within its Coastal limits is called Integrated Coastal Surveillance System (ICSS) and is used to ensure regional security and assist friendly navies by monitoring maritime activity in the Indian Ocean. This combined with Coastal radars in Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Seychelles, Bangladesh, and Maldives gives India and other partner nations a comprehensive view of the maritime traffic. India has also developed the Information Management and Analysis Centre (IMAC) which includes a fusion centre for all the data collected by these stations, also known as Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Here the data is processed to generate valuable insights to aid maritime domain awareness of India and partner countries. This centre has liaison officers from 12 Nations including France, Italy, Japan, U.K and the U. S (IFC-IOR, 2024). India has planned set up 104 radar stations in its coastline of which 46 are operational. India has also proposed to develop more coastal stations in Myanmar, Thailand, and Philippines as well. The number of stations that are operational in littoral states in Indian Ocean are as follows.

Table 2: Deployment of Coastal Radar Stations by India (Overseas). Source: (Drishti IAS, 2020)

| Country | Number of Coastal Radar Stations |

| Maldives | 10 |

| Bangladesh | 20 |

| Seychelles | 5 |

| Sri Lanka | 6 |

| Mauritius | 8 |

India is also strengthening its position in IOR by bolstering its naval bases like Karwar (INS Kadamba) in the Western coast, which is planned to be built to be at a cost of $3 Billion as the largest naval base in the Eastern hemisphere after completion of Phase 2B of Project Seabird (AECOM, 2019). In the Eastern Coast, India is building a new naval base under Project Varsha, which is destined to be the home of Indian Navy’s new fleet of nuclear submarines, in Rambili in the state of Andhra Pradesh (Asia Times, 2024). To be named as INS Varsha, will house a large nearby-by facility of Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) that will provide modern nuclear engineering support facility to India’s new Arihant class nuclear submarines (SSBNs) eventually to be housed there. This base is compared to the top-secret Hainan nuclear submarine base of Chinese PLA Navy.

These developments showcase India’s ambition to develop a blue water Navy to secure its maritime interests, to have effect hold over key choke points as mentioned in its Naval doctrine, compete with emerging players, and maintain a presence in strategic positions. Thus, India effectively displaying the Sea Power Theory in action. Whereas these developments can be safely concluded as India’s reaction to security deprivation caused by increasing Chinese influence, setting in motion actions to undermine China’s interests as well, which is true in the case of Security Dilemma theory. Here, both powers are escalating their actions to undermine each other’s security interests, increasing their insecurity, and enabling an arms race as well.

Figure 5: Juxtaposing both strategies reveal Chinese encirclement of India has been neutralised.

3.4 Diplomatic Initiatives and Alliances:

Along with Military augmentation, India has also stepped up its diplomatic initiative, especially in developing alliances with like-minded powers, entering strategic partnerships with littoral countries, and conducting regular multilateral and bilateral exercises. Especially under the current government in New Delhi, many diplomatic initiatives have been designed specifically for bolstering India’s maritime relations with partners in the Indian Ocean. One of the keystones in India’s IOR policy is the ‘Security and Growth for All in the Region’ (SAGAR) doctrine which advocates for a “free, open, inclusive, peaceful and prosperous” region. Under this policy, India aims to be a net security provider to littoral states as well as be the first responder to natural disasters along with being a natural economic partner. This is also indicative of New Delhi embracing the geostrategic concept of ‘Indo-Pacific’, where the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific is viewed as a single strategic theatre (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). India is the founding member of 23-member Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) that is primarily created for to promote economic objectives, has emerged as key multilateral platform for maritime security and governance. India sought to revive this body as part of regional leadership strategy as this platform is considered as a mechanism to contain Beijing’s influence (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024).

India has provided relief to many littoral states during their hours of crisis. Like for instance, India has extended more than US$4Billion to Sri Lanka during the economic crisis of 2022 (Diplomat, 2023). Maldives was provided with 2400 tonnes of drinking water during its worst water crisis in 2014, when its Male Water Treatment plant was defunct due to a massive fire (Business Today, 2024). Such activities have earned New Delhi some goodwill.

India is also participating in Naval exercises in the Indian Ocean and in ‘mini-lateral’ efforts with like-minded countries. Let’s take look at the exercises done by Indian Navy with its partners and compare it with Chinese Navy in Indian Ocean region (IOR).

Indian Navy:

| Exercises | Navy/Navies | First Edition | Total Editions |

| Malabar Exercise | India, U.S, Japan, and Australia | 1992 | 26 |

| Varuna | India and France | 1993 | 21 |

| SIMBEX | India and Singapore | 1994 | 28 |

| MILAN Exercise | Multilateral Exercise | 1995 | 12 |

| INDRA Navy | India and Russia | 2003 | 12 |

| SLINEX | Sri Lanka and India | 2012 | 8 |

| CORPAT | India, Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar | 2002 | 5 |

| AUSINDEX | India and Australia | 2015 | 5 |

| Konkan Exercise | India and U.K | 2004 | 16 |

| IMCOR | India and Myanmar | 2013 | 8 |

| IBSAMAR | India, Brazil and South Africa | 2008 | 7 |

| Exercise La Pérouse | India, France, Australia, Japan and U.S | 2023 | 1 |

| JIMEX | India and Japan | 2012 | 11 |

| BONGOSAGAR | India and Bangladesh | 2019 | 5 |

Table 3: Exercises Participated by Indian Navy in Indian Ocean Region. Source: (Press Information Bureau of India, 2024).

Chinese Navy:

| Exercises | Navy/Navies | First Edition |

| Joint Sea Exercise | China and Russia | 2012 |

| Peace and Friendship | China and Malaysia | 2015 |

| Maritime Cooperation Exercise | China and Pakistan | 2014 |

| Exercise Blue Whale | China and Tanzania | 2010 |

| Exercise Aman | Multilateral hosted by Pakistan | 2007 |

| Exercise CUES | China and ASEAN | 2014 |

| Maritime Silk Road | China and Indian Ocean Littoral state | 2013 |

| Exercise Blue Sword | China and Thailand | 2005 |

| Exercise Security Bond | China, Russia, and Iran | 2023 |

Table 4: Exercises participated by Chinese Navy in Indian Ocean. Source: (China Military, 2024).

It is to be noted that, India has increased military engagements with its partners specifically after 2000, coinciding with increasing Chinese presence in the region. China on the other hand has increased such exercises with countries in the region post 2010, marking its expansion of interests in Indian Ocean. This increase in activities of both navies is in line with the Security Dilemma theory, where both powers display their power of diplomacy, military might and naval prowess through simulated exercises and live-fire trails. For example, China has attributed Malabar Exercise as “Asian NATO” and has criticised the QUAD for indulging in isolating Beijing (Kobierski, 2020).

As we speak of QUAD, which is known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, is a partnership between India, the U.S, Japan, and Australia. Though started as a platform to assist littoral states on the eve of 2004 Tsunami, by 2007 had transformed into an economic and strategic partnership (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024). Integration of Malabar Exercise into QUAD, gave it a militaristic profile, which has not gone down well with Beijing. Besides this, India has multiple engagements with same partners of QUAD, such as India-Japan-US Dialogue, the Australia-India-Indonesia Trilateral Dialogue etc. This points out to India’s offshore balancing efforts to contain Chinese rise, which is in line with the Sea Power theory, where one country cultivates alliances with stronger powers to balance the revisionist power.

This chapter has showcased India’s strategic initiative which acts as defences against the Chinese rise in the Indian Ocean region. India has developed coastal radars, building up bases in and around Indian coasts, modernising its Naval prowess and is actively cultivating alliances with like-minded powers in the region. Overall, with the creation of bases and gaining access to many ports in the region, India has mostly neutralised China’s designs in the region, but it may have a long way to go with regards to sheer number of assets deployed and naval modernisation.

Chapter-4: Assessing the Effectiveness of India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” Strategy- Case Studies

In this chapter, I will examine the effectiveness of the ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ strategy in protecting India’s national security and maritime interests. Here I will be looking at implementation of this strategy in Mauritius, Philippines, and Maldives, to ascertain the effectiveness by looking at their response to Indian government’s concerns and how the relationship has evolved over the years. By the end of this chapter, I will draw conclusions on the success/failure of the strategy and explain why it has turned out to be like that. I will be starting with Mauritius, where analysts have claimed that India had been more successful than any other country.

4.1 Mauritius:

Relations between India and Mauritius are longstanding, based on a shared civilisational heritage and common kinship and culture. These relations are categorised as “unique and special.” They have also been called “sacred and umbilical” (Ganapathi, 2015). The relations have always been very cordial, and Mauritius plays an important part in extending India’s reaches way towards the south of Indian Ocean. The major highlight of India’s success in Mauritius is arguably the setting up of a new airbase and a jetty in the Agaléga Island, which is located 1100 km north of the main islands. The base and jetty were inaugurated by Prime Minister Modi of India and PM Pravind Jugnauth of Mauritius on 29th February 2024 (Pant & Bhattacharya, 2024).

This infrastructure is critical, given the island’s location. The archipelago of Agaléga is surrounded by Seychelles to the North, Maldives, Diego Garcia and Chagos Island to east, Madagascar, the Mozambique Channel, and entire Eastern Coast of Africa to the West (Pant & Bhattacharya, 2024). A base here would enable India to monitor maritime terror activities emanating from Africa, piracy, narcotics trade as well as keep an eye on Chinese movements in the region. The infrastructure built in this island will put an end to India’s long-standing quest to establish a naval facility in the centre of Indian Ocean (Sen, 2024). These new facilities will bolster India’s image as a Maritime power. Indeed, it will be as the new landing strip is specifically designed to station Indian Navy’s P-8I maritime patrol aircraft, which were usually in French Reunion Island (Sen, 2024). The stationing of this long-range patrol aircraft gives India a significant edge by providing a vantage point in Indian Ocean. The airbase and jetty are accompanied by intelligence institutions and transponders that will be used to identify ships to reinforce Maritime Security. The islands sit at key entry points in the Western Indian Ocean like Mozambique Channel and Cape of Good Hope, while the Suez Canal is not that far, make it incredibly crucial for India to establish its infrastructure there (Pant & Bhattacharya, 2024). With Maldives veering towards China, and Seychelles denying setting up of bases in Assumption, Agalèga is a satisfying victory for India.

Yet India’s relation with Mauritius is not just about this infrastructure, as one can say that this base is a culmination of India’s success in building crucial aspects of the relationship. India has over the years built many civic infrastructures in Mauritius like the Supreme Court Building, Metro Express rail, an ENT Hospital, funded Social Housing and healthcare projects (Revi, 2020). The initiatives like SAGAR, assistance during Covid-19 as well as during Oil Spill disaster in 2020, had garnered goodwill of both government and as well as the people (Sen, 2024).

If we are to apply the Sea Power theory, to check the effectiveness of India’s strategy in Mauritius, we can see that in terms of these aspects of the theory:

- Control of Strategic locations: the development of military infrastructure in Mauritius, such as the Agalèga Islands, enhances India’s ability to monitor and secure the southwestern Indian Ocean. India enhanced its strategic depth and ability to control critical sea lanes, aligning with Mahan’s principle of controlling strategic locations (Mahan, 1898).

- Naval Presence: India’s naval deployments in the region, supported by the development of the Agalèga Islands, enhance its operational capabilities and readiness to respond to security threats. The strategic infrastructure boosts India’s naval strength and capability like deployment of Navy’s P8-I MPA, ensuring effective surveillance and response mechanisms.

- Maritime Commerce: The Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and Partnership Agreement (CECPA) between India and Mauritius facilitates trade and economic cooperation, strengthening India’s economic influence in the region (Revi, 2020). Enhancing maritime commerce is crucial for maintaining sea power. The CECPA agreement ensures secure and beneficial trade routes, supporting India’s economic interests.

- Alliances and Bases: India’s close diplomatic relations and defence cooperation with Mauritius, including joint naval exercises and maritime security initiatives, strengthen bilateral ties and provide a platform for a sustained naval presence. Establishing strong alliances and bases is a core aspect of sea power (Mahan, 1898). India’s strategic partnerships with Mauritius enhance its influence and operational capabilities in the region.

Applying Sea Power Theory to evaluate India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy in Mauritius reveals that India’s strategic initiatives effectively enhance its maritime security, control over critical sea lanes, and regional influence. The development of the Agalèga Islands, strengthened naval capabilities, economic agreements, and strategic partnerships align well with Mahan’s principles of sea power, contributing to the overall effectiveness of India’s strategy in countering Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean region.

This case also meets aspects of the Security Dilemma theory as well.

- Perception of Threats: India perceives China’s “String of Pearls” strategy, including investments and port developments in the Indian Ocean, as a strategic encirclement that threatens its maritime security. Consequently, India’s response includes establishing military bases and enhancing alliances in the region.

- Action-Reaction Dynamics: India’s development of the Agalega Islands in Mauritius is seen as a countermeasure to China’s presence in the region. This has led to China potentially increasing its investments and diplomatic efforts in neighbouring countries to maintain its strategic advantage (Dutta & Choudhury, 2024).

- Strategic Balancing: While Mauritius has generally been supportive, there is still a regional perception that such developments contribute to militarisation and increased tensions. In 2020, Massive protests broke out in Mauritius against Indian infrastructure development, stating ‘loss of sovereignty’ as the major reason, showcasing the security dilemma within Mauritian Civil society about increasing militarisation and tensions (Pant & Bhattacharya, 2024).

Applying Security Dilemma Theory to India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy in Mauritius reveals the complexities of regional security dynamics. While India’s strategic initiatives aim to enhance its security and counter China’s influence, they also contribute to a cycle of action and reaction that can escalate tensions and potentially destabilize the region.

To draw a conclusion, it can be safely assumed that in Mauritius, India’s strategy has paid off and is effective in protecting its valued interests. Yet, the cycle of escalation unleashed by India’s actions means, there can be more Chinese activity in the vicinity in the coming few years.

4.2 Philippines:

Philippines presents itself as the perfect host to extend India’s geopolitical interests to China’s immediate periphery. As India seeks to enhance its presence as a credible defence partner in Southeast Asia and wider Indo-Pacific, Philippines can be a good place to start (Pant, 2024). Under Ferdinand Marcos Jr, Philippines is rapidly shedding its China dominated outlook of its previous President Duterte to a more multi-aligned foreign policy, where it is increasingly diversifying its security and economic ties from U.S as well (Pant, 2024). Thus, India’s intent to play a proactive role in the Indo-Pacific coincides with needs of Philippines. India, since 2014 has been more vocal about the plight of the Southeast Asian nations and China’s growing belligerence in response to China’s increasing presence in Indian Ocean, especially India’s support for UNCLOS and 2016 Arbitral Award on South China Sea that was in favour of Philippines (Saha, 2023). Philippines had openly defined China as a ‘serious concern’ in its National Policy 2017-2022 and this converges with India’s strategy in the region (Observer Research Foundation, 2020).

The highlight of this relationship is marked by the $375 million contract signed in 2022 to supply 3 batteries of the shore based anti-ship supersonic BrahMos missile system to the Philippines Army (Pant, 2024). India had started delivery of these system in early 2024, highlights the first step of it being a key defence player is Southeast Asia. These systems are highly potent given the fact that it is one of the fastest long-range cruise missile systems developed by India and Russia and is used as deterrent against Chinese naval activities in West Philippine Sea. China had started challenging Philippines in South China Sea, and there is a rise in that trend post the Arbitration Award of 2016. Its militarisation efforts have been altering geography and balance of power in the region through gray zone manoeuvres (Saha, 2023). Also, China, by strengthening its hold in South China Sea can have greater power projection in Eastern Indian Ocean as well, which can be detrimental for New Delhi. This system can play a crucial role in deterring China from crossing that line. Thus, this development highlights increasing strategic relations between India and Philippines, founded on the mutual understandings as ‘victims of Chinese aggression’ (Observer Research Foundation, 2020).

When we apply the Sea Power theory to evaluate the effectiveness of India’s “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy in countering China’s “String of Pearls” in the Indian Ocean region, focusing on strategic interactions with the Philippines, these are the observations that I found.

- Control of Strategic Locations: The Philippines is strategically located in the South China Sea, a crucial maritime corridor connecting the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Although the “Necklace of Diamonds” primarily focuses on the Indian Ocean, India’s engagement with the Philippines indirectly supports its broader strategy. Enhanced cooperation and naval presence in the Philippines, such as joint maritime patrols and port visits, help India monitor and secure critical sea lanes.

- Naval Strength and Capability: India’s naval modernization efforts, including the acquisition of advanced submarines and maritime surveillance systems, have been showcased in joint exercises with the Philippines. These exercises often include elements that enhance operational interoperability and readiness, indirectly benefiting the Philippines’ maritime security. The supply of Indian BrahMos missile system to Philippines can help them establish a strong deterrence against Chinese belligerence.

- Maritime Commerce: While the Philippines is not a direct beneficiary of India’s economic strategies under the “Necklace of Diamonds,” India’s broader goal of ensuring secure sea lanes indirectly supports the Philippines’ maritime trade. India’s efforts to secure the South China Sea through diplomatic and military cooperation contribute to regional stability, benefiting all littoral states, including the Philippines.

- Alliances and Bases: Strengthening alliances with the Philippines enhances India’s strategic depth in the region. Joint military exercises and defense agreements, such as the recent BrahMos missile deal, illustrate this cooperation. These alliances are critical in projecting power and maintaining a presence in strategic maritime regions, aligning with Mahan’s principles.

Applying Sea Power Theory to the context of the Philippines underscores the importance of strategic locations, naval strength, maritime commerce, and alliances. Although the primary focus of the “Necklace of Diamonds” is the Indian Ocean, India’s strategic interactions with the Philippines enhance regional security and stability, indirectly supporting its broader maritime objectives.

These developments also support the components of Security Dilemma theory as well, as the Philippines is directly affected by the strategic manoeuvres of both India and China. The Philippines’ security policies and alliances are influenced by these regional dynamics.

- Perception of Threat: The Philippines may view India’s naval presence and alliances in the Indian Ocean as a balancing force against China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. However, this can also lead to increased tensions and a regional arm race.

- Response and Alliances: The Philippines has sought to strengthen its alliances, notably with the U.S and other key players like India and enhance its own maritime capabilities. India’s strategic actions indirectly support these efforts by providing a counterbalance to China.

- Regional Security Dynamics: The presence of Indian naval assets and increased cooperation with Southeast Asian countries can contribute to a more multipolar security environment, potentially stabilizing or further complicating regional security.

Applying the Security Dilemma Theory to the “Necklace of Diamonds” strategy in the context of the Philippines reveals the complex interplay of regional security dynamics. While India’s strategic initiatives can mitigate some security concerns by countering China’s influence, they can also contribute to heightened tensions and a security dilemma in the region.

To conclude, in the case of Philippines, India’s strategy of ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ appears to have worked positively, given the mutual concerns the parties have about China, yet New Delhi’s initiative to arm Philippines and neighbours like Vietnam has direct correlation to China’s consistent arming of Pakistan, India’s arch-rival, depicting the consequences of Security dilemma between India and China. These developments can also trigger further reactions from Beijing to undermine India’s security.

4.3 Maldives:

The India-Maldives relationship have seen many ups and downs in the last decade. From the highs of the Solih Government of 2018-2023 to the lows of 2023 under the new Muizzu Government, the relationship has come to a full circle. Recently, the relations turned unusually sour, when Maldives saw Modi’s visit to Lakshadweep Islands (Indian islands close to Maldives) as an attempt to project it as an alternative tourist destination to the Maldives. In the process, derogatory remarks by Maldivians against Indians and the Prime Minister were made, which led to a strong reaction in India (Pant, 2024). As some of these comments came from serving Deputy ministers in Muizzu Government, reactions from Indian government were fierce. Nevertheless, Muizzu government apologised for the comments and both governments have moved on ever since the incident, even President Muizzu was invited for PM Modi’s third term inauguration, yet there is palpable friction in the engagements. Current President Muizzu stormed into power on the back of “India-out”campaign that he and his party supported against over reliance on India economically and because of this, such rhetoric was expected (Basarkar, 2024). Right after being elected, Muizzu chose to visit Turkey first instead of India (breaking a long-held tradition of his predecessors) and then to China. He sprang into action to realise his poll promise of removing Indian military personnel manning the India-gifted aircrafts and signed 20 new agreements with Beijing spanning from financial to military projects (Basarkar, 2024).

China has increasingly utilised this new opportunity to anchor its position in Maldives, as it is beneficial for Beijing, as Male sits along the busiest trade passages in the world where 80% Chinese oil imports flow through. China had got the better of Maldives under Abdulla Yameen’s rule (2012-2017), when it signed an FTA, which was later stalled by Pro-India Solih government (Basarkar, 2024). Chinese research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 03 was given permission by Maldives to dock at Male, which clearly raised eyebrows in New Delhi (Revi, 2024). All these developments, particularly in the last 10 months points towards the impact of Election Politics in bilateral relations. India has been the target of several election campaigns in its immediate neighbourhood, where Maldives is just another case (Revi, 2024). Analysts believe that Muizzu’s endgame is not replace India with China, but to use them to get a better deal for his country (Basarkar, 2024). Here, Maldives is exploring other options instead of relying on India, and seeks to expand ties with Turkey, UAE among other players. Though, it has not completely cut off from Indian initiatives as it still takes part Military exercises as well as India is still its biggest Maritime Security partner, biggest trade partner and traditional donor. Recently, India has cut its budgetary support to Maldives for reasons that were not specified (Firstpost, 2024).

Given the situation, it can be safely assumed that the relations between India and Maldives have hit some turbulence, and is unfavourable for India’s strategy so much so that, India had opened a new naval base in Lakshadweep Islands to mitigate the loss of influence in Maldives (Pant, 2024).

When applying Sea Power Theory, we can see that India struggles to meet certain conditions like:

Control of Strategic Locations: The Maldives, located near vital sea lanes in the Indian Ocean, is strategically significant. However, India’s efforts to establish a strong presence in the Maldives have been challenged by political instability and shifting allegiances.

- Political Instability: Frequent changes in the Maldivian government have affected India’s ability to maintain a consistent strategic presence. For instance, the pro-China administration under President Abdulla Yameen signed significant agreements with China, including the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in 2017, undermining India’s influence. Current government has also taken a very anti-India stance right from the get-go.

- Shifting Allegiances: The Maldives’ strategic location has made it a focal point for Chinese investments under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has resulted in the Maldives tilting towards China during certain administrations (Basarkar, 2024).

Naval Strength and Capability: Despite India’s naval modernization efforts, its ability to project power in the Maldives has been limited by China’s growing naval presence and economic influence.

- Chinese Naval Presence: The increasing presence of Chinese naval assets in the Indian Ocean, including port visits and maritime patrols, has posed a challenge to India’s efforts to dominate the region.

- Economic Leverage: China’s economic investments in Maldivian infrastructure, such as the development of the Hulhumalé Island and other key projects, have strengthened its influence, making it difficult for India to assert its naval superiority (Revi, 2024)

Maritime Commerce: The Maldives’ economic dependence on tourism and foreign investments makes it susceptible to external influences, particularly from China.

- Economic Dependence: China’s significant investments in the Maldivian tourism sector and infrastructure projects have increased the Maldives’ economic dependence on China, diminishing the effectiveness of India’s economic and strategic initiatives (Pant, 2024). This was particularly seen in the recent fiasco.

- Strategic Projects: Projects like the Sinamale Bridge (China-Maldives Friendship Bridge) have further cemented China’s economic foothold in the Maldives, challenging India’s efforts to enhance its maritime commerce and influence (Basarkar, 2024).

Alliances and Bases: India’s efforts to establish a military base in the Maldives have faced significant obstacles.

- Military Base Challenges: Proposals for Indian military bases in the Maldives have met with resistance from local political factions and public opinion, which view such moves as a threat to national sovereignty.

- Diplomatic Setbacks: Diplomatic efforts have been inconsistent due to the fluctuating political landscape in the Maldives, with some administrations favouring closer ties with China, thereby limiting India’s ability to secure strategic military agreements.

When applying the Security Dilemma theory, I find these observations where India’s efforts to secure its maritime interests have prompted reactions that complicate its strategic goals.

Increased Tensions and Counteractions:

- Maldivian Domestic Politics: India’s attempts to increase its influence in the Maldives have sometimes been met with resistance due to domestic political dynamics. The Maldives has seen fluctuating political administrations, some of which have been more aligned with China, leading to a volatile environment for Indian strategic interests (Revi, 2024).

- Chinese Countermeasures: China has responded to India’s strategic moves by increasing its own presence and investments in the Maldives, such as the development of infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Basarkar, 2024). This has exacerbated the security dilemma, with both India and China viewing each other’s actions as threats, leading to a cycle of countermeasures.

- Economic and Military Influence: India’s efforts to establish a military presence and economic influence in the Maldives have sometimes backfired. For example, the ‘India-out’ campaign in the Maldives saw a pro-China government taking power, which was critical of Indian interference, illustrating the counterproductive effects of the security dilemma (Basarkar, 2024).

The Security Dilemma Theory suggests that India’s strategic initiatives, aimed at enhancing its security and countering China’s influence, inadvertently escalate tensions and provoke counteractions from China and local political actors in the Maldives. This resulted in a paradox where efforts to increase security led to greater insecurity and instability.

4.4 Evaluation:

From the above case studies and the application of both Sea power theory and Security dilemma theory in them, it becomes clear that India’s strategy of necklace of diamonds is successful in certain countries and has failed in others. While inspecting the effectiveness, it has revealed certain strengths of the strategy as well as limitations of it. Also, it revealed the factors that can affect the success of the strategy.

During my analysis of the ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ with the application of Sea Power theory, there are some characteristics that this strategy fulfils, while it falls short in fulfilling others. Let’s look at the characteristics that it fulfils. With regards to the first criteria of Sea Power theory, Control of Strategic Locations; India’s strategy is mostly effective as it has firm grip over the Choke points in India Ocean, for instance developing bases in Agalèga Islands in Mauritius helps India to keep an eye on Mozambique Channel, access to Duqm in Oman, and Chahbahar in Iran in the case of Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb and Strait of Hormuz respectively. In the East, bases in Andaman and Nicobar Islands and access to Changi Naval Base in Singapore keeps India’s control over the Malacca strait intact. Thus, in this front, India’s strategy has been quite successful as per the Sea power theory. Second, in terms of Alliances and bases, India has been able to develop both in reaction to Chinese surge. India has developed alliances with powers like the U.S, Japan, Australia in the format of QUAD, it has strengthened partnerships with France, Germany as well as the U.K, who have key interests in the region. All these partnerships have the implicit goal of restricting and balancing the Chinese rise.

Yet this strategy does not fulfil other criterions of Sea power theory, for instance with regards to Naval strength and capability, as India cannot simply match the sheer number of assets that China has developed and is currently developing. India’s area denial capability via submarines is questionable, thanks to smaller numbers of it with the Indian Navy. In terms of technology, Indian Navy lacks the bite to take on Chinese Navy on the high seas. Another criterion that this strategy has failed to fructify is the improvement of Maritime Commerce. As mentioned in (Baruah, et al., 2023), India may have improved its trade relation with littoral states in the region, but it is no longer the largest trading partner of the region as China has taken lead since the early 2010’s. India has not been able to capitalise its position despite impressive economic growth, as research pointed out dipping share of trade for the country in the same time period.

Thus, under the aegis of Sea Power theory, India’s strategy is a mix of both success and failures as it meets some criterions while it doesn’t others. Complex political instability in littoral states like Maldives; and India’s own resource constraints in the case Naval development, put the strategy at risk of being ineffective.

My analysis also revealed another facet of this ongoing competition, when applying Security Dilemma theory, it was found to function at two different levels. The first level is obvious, where each action of both China and India to undermine the security evokes a similar counter reaction. China’s efforts to encircle India in the early 2010’s has been befittingly replied to by the Indian administration, which now has started to extend its presence into South China Sea through Philippines. Also, China’s constant arming of India’s rival Pakistan, has made India returning the favour by arming Philippines, and potentially other Southeast Asian countries, who are now increasingly interested in Indian Weaponry. Also, India’s increasing counter activity has led China to directly challenge India, by sending its research vessels to the ocean, when India announces any missile tests, as well as docking them in littoral states. This points towards the fact that, in pursuit of undermining each other’s security, both parties have set the ball rolling for an arms race as well as the cycle of escalation, that is not only between them, but also one that include the littoral states. This is evident in India supplying patrol boats to Vietnam to counter China, transfer of a submarine to Myanmar to counter Chinese supplied submarines to Bangladesh etc (The Diplomat, 2020). Thus, this strategy of India, may be effective in countering China’s nefarious designs in the Indian Ocean for now, yet it has set off an inadvertent cycle of actions that can aid to its insecurity in the region.

In the second level, there is an interesting phenomenon that is taking shape within the littoral states who are inadvertently part of both strategies of China and India, who have started to push back against these designs of both countries. In many of these states, people are getting increasingly concerned about the erosion of sovereignty and unsustainable economic fallouts that emanates out of this. This was specifically seen in the case of Maldives, whereby the Security dilemma had set in about their sovereignty, that people took out the ‘India-out’ campaign. Similarly, in Seychelles, the current government had denied India access to Assumption islands, fearing the loss of sovereignty (Sen, 2024). Such similar setbacks are also dealt by China as well, particularly in Gwadar, Pakistan, where local Baluchistan Militia had carried out attacks on Chinese engineer convoys in the last few years (The Japan Times, 2024). All this points towards to increasing security dilemma that is emerging within the participating states.

To conclude, the ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ strategy may have been successful in certain cases, whereas it may have failed in some other, yet it can be stated as a ‘work in progress’ project for India. Its success depends heavily on the political aspects of the littoral countries. The investigation also revealed that it might be effective in securing India’s security in the short term, but it may lead to escalation of tensions in the long term. Yet, I firmly believe there isn’t many options available for India as well, other than to proceed forward, where both competitors reach an saturation point of escalation, that may stabilise the region like what happened during the Cold War

Chapter-5: Conclusion

5.1 Summary of Key findings:

In my investigation on the important aspects of ‘Necklace of Diamonds’, I have encountered many aspects of the strategy that underpins its success in countering China’s rise. There are multiple key findings that have been unravelled by this research into the effectiveness of India’s strategy in countering China’s hegemonic designs and efforts to challenge India’s position in the Indian Ocean region. In a systematic manner, we have tried to understand the strategies of both India and China, what are the factors that necessitates them to acquire more power and influence in the region, key reason being the protection vital sea lines of communications (SLOCs). We understood the security concerns that India has vis-à-vis China’s expansion of influence, with Beijing setting up military bases, sending survey vessels, spy ships which undermines India’s interests. We then analysed India’s strategic initiatives in the Indian Ocean that includes strategic bases, naval modernisation, diplomatic engagements, and alliance partnerships, and briefly compared it with China’s assets in the region. These initiatives were analysed with both Sea Power Theory and Security Dilemma theory to ascertain the nature of it. Also, with case studies, we checked the effectiveness of the strategy in countries like Mauritius, Philippines, and Maldives, where again Sea Power theory and Security Dilemma theories were applied to see the dynamics of India’s relationship with them.

5.2 Final Thoughts: